Books Have Always Been Sus, But With AI Now More Than Ever

What is a book? Will AI destroy the world? Can I ever love again?

This post is dedicated to Larry McMurtry (1936-2021), a bookdealer and sometime author. You may listen to the audio version here:

In Time of 'The Breaking of Nations'

by Thomas Hardy

I

Only a man harrowing clods

In a slow silent walk

With an old horse that stumbles and nods

Half asleep as they stalk.

II

Only thin smoke without flame

From the heaps of couch-grass;

Yet this will go onward the same

Though Dynasties pass.

III

Yonder a maid and her wight

Come whispering by:

War’s annals will cloud into night

Ere their story die.“These strange days did not just happen. We, and those in power, created them together.”

The video above is only a few seconds long, and will help you into a mindframe useful to understanding this post. Also, you should watch all six episodes of Adam Curtis’ BBC documentary Can’t Get You Out Of My Head. If you doubt, let me reassure you by saying that the BBC were not at all happy with Curtis’ work, and pushed it straight to their streaming service.

YouTube philosopher Jared Henderson recently made a video entitled Kindle has a big problem, so I’m leaving it behind. He begins the video reminding us of the now-famous 2009 instance in which Amazon, without any notification, deleted a bootlegged edition of 1984 from the Kindles of customers who had bought the book in good faith. I remember when this happened; in fact, I owned a used bookshop at the time, and felt vindicated in my refusal to buy a Kindle or read e-books. The fact that 1984 was the title deleted only fueled the viral fire, which I imagine could only have burned brighter if it had been Fahrenheit 451.

In his video Henderson reminds viewers that, according to Amazon TOS, no one actually owns a Kindle book. Rather, they have purchased an individual license to access an electronic file. To be clear, there is no big crisis or recent change over at Amazon. Henderson was simply reminded of something that already bothered him, which is that Amazon can alter the licensed file at will (not to mention changing their TOS however and whenever they like). His e-copy of the first volume of The Wheel of Time had its cover changed to promote an Amazon series, and this was his final straw. He has abandoned a library of fifteen hundred titles, and I think it was a good decision.

Abandoning Kindle is as much a rejection of electronic reading as abandoning Amazon would be a rejection of bookshops, which is to say, not at all. E-books will, and should, become more and more common. Heck, even I have read an e-book or two at this point (not to speak of the several I’ve read to record audiobooks1).

At the end of his video, Henderson told the audience of three steps he would be taking toward change in the near future, but stopped short of calling for the fall of Jeff Bezos (he claimed not to own any pitchforks). First, he would look for a way to change his affiliate links. Second, he would focus on what he called localism: not only buying from local bookstores, but also digital localism. “So e-books, audiobook files, whatever it is that I could possibly own, I will have it stored locally so I can access it when I want, and no giant corporation could ever take that from me.” Third, he would “spread the word”, which I suppose would consist of encouraging others to take similar steps.

L. M. Sacasas recently posted The Cat in the Tree: Why AI Content Leaves Us Cold. I commend his Substack to you. In The Cat in the Tree Sacasas meditates, mostly positively and gratefully, on the power of humanity and art as it can be expressed through artificial intelligence. Mid-way through his meditation, he says

Now it seemed to me that so much of our conversation around the capabilities of artificial intelligence have been misguided, focused as they were on its approximation of human virtuosity. Can it excel as the best of human artists? Can it fool us by its predictable perfection? But a simulacra of human virtuosity is not what we need. We need each other. We need signs of life about us. We need to know that we are not alone. And this is something we must consider not just in relation to the singular artifact, but also in relation to our environment. In a time of acute loneliness, the proliferation of AI-generated content seems not unlike an act of pollution, compromising the integrity of the social ecosystem.

We need each other. We need signs of life.

Sacasas considers that he had not sufficiently appreciated as a sign of life an AI video he had seen one recent morning. Regardless of whether AI had been used or not to produce the video, here was art from someone in the each-other-aether that could genuinely provoke wonder.

Sacasas was seeking to be grateful, so far be it from me to do otherwise. The use of AI has already benefited me in projects both technical and creative; I am excited to see it used for truth, beauty, and goodness. Nonetheless, we must acknowledge that it is almost certainly going to break our world2.

When Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok are flooded with girls-next-door who are nothing more than simulacra (not to speak of simulated parodies thereof on OnlyFans) and the last honest man has purchased a course on how to generate and sell AI-generated ebooks on Amazon, shall we give up on any possibility of real knowledge?

No. I have great hopes for this breaking of the world. We simply need each other. We need signs of life.

A generation ago, early 2000s, pundits and knowledge-brokers started talking about Web 2.0. This was the “participative web”, a ballyhooed world of potential community that turned quickly to a world of user-generated content, blogs and wikis and sharing sites.

Web 2.0 was bullshit. Rather than being the place for community that many promised, the term was a way of helping the offline hoi polloi conceptualize the interactivity of the massive market they were being made part of. Gamers and nerds of all sorts already had plenty of online community. T1 lines were not uncommon among twenty-somethings in the 90s, and not just for LAN parties. People left their wifi networks unprotected on purpose. I, and many like me, read William Gibson, Cory Doctorow (before BoingBoing and his YA phase, which were cool too), Philip K. Dick. We knew about the internet of things before it was a thing; we formed clans before World of Warcraft was a gleam; we formed allegiances by continent and time zone (Eastern Standard Tribe) and anyone who wanted a VPN had one.

I was not a true denizen of the internet, at least, not in the pocket protector sense; certainly I was no architect, and had no pretensions to be. To draw a distinction that has grown fuzzier over the years with the emergence of more and more nerddoms and fandoms, I was less a geek and more a nerd. Still, it took me years, and some wifely prodding, before I finally brought myself to put a password on my wifi. In my conception, the internet was something we were all building together, and it had, at least ideally, a moral code of mutual support. Sorry, neighbors, for cutting off your wifi; I broke the ethos, but so did everybody else, eventually.

In the mid and late 90s I hung out on killdevilhill.com and The Jolly Roger, and it was just as this archived New York Times piece from 1997 described it:

There are thousands of Web sites, Usenet groups, and mailing lists devoted to literature on the Net, and what emerges is a true revolution in literary criticism -- the cracking of hidebound ivy walls of academia and the scholarly press. Suddenly what was the province of a relatively small group of well educated people has been thrown open to anyone who can read and think. Buy a copy of Ulysses, read it, go on the Web and write an analysis of Leopold Bloom's lunch. And find a receptive and reactive audience…

“While it has often been tough to find good conversation in the bars and cafes around Chapel Hill, it has never been so on our Web sites,” says Elliot McGucken, president of the North Carolina-based Kill Devil Hill site, named for a hill on Cape Hatteras and billing itself as “The World's Largest Literary Cafe.” “We are now serving over 1,000,000 page views a month, and the day has long ago passed when we were able to keep up with all the interesting posts and cool conversations.”

That's certainly an understatement. KillDevilHill.Com and two related sites -- Western Canon University and The Jolly Roger, two avowed pro-Western canon communities that make little room for modern literature -- teem with discussion, the kind that goes well beyond freshman lit 101. On the Mark Twain discussion board, a visitor wonders aloud about the “aspects of nature” in the Royal Nonesuch performance in Huckleberry Finn. There are arguments over William Shakespeare's childhood in the Shakespearean section. Over on the Herman Melville board, posters discuss Ahab's use of the sea chart as a controlling mechanism and Ishmael's artistic nature.

Some of the posts are simplistic, others amazingly complex. Of course, there are dozens of students looking for insight for their high school and college papers. The experience is almost entirely text-based (on the message boards, the only graphics are advertisements) and that's part of the aim, says McGucken, who calls the Web “the only technological medium that's rooted primarily in the printed word.” The sites pointedly concentrate on what he calls the permanence of the Great Books over the transience of pop culture.

“It's cool to think that our sites will never be outdated," he says. "And that's what's so much fun about the Kill Devil Hill experience, where you can't click on the mouse without encountering someone's take on some aspect of one of the Great Books. Not all the posts are brilliant, nor are they all profoundly introspective, but they are all enamored, and they are often enough from good-natured, curious seafarers who are only trying to find out if somebody else, somewhere in the world, sees the same beauty in words reflecting a more somber reality.”

Then Web 2.0 came along, and everyone was ported onto massive social websites. Everyone and their grandma joined, and forums became a nostalgic joke. We made ourselves product to be sold, and started pages and groups for sonnet lovers on the same site on which we posted baby pictures. Grandma never visited the old sites; on these massive new sites we muted grandma’s comments.

Old social sites like Kill Devil Hill were little worlds unto themselves, worldlets in which every being was a lover of sonnets; we teleported in and out, visiting at our leisure. Then Web 2.0 came along, and sites like Facebook became the whole entire world, and sonnets went back to their corner.

We drew closer to the singularity.

Some say Web 3.0 has already come along, but if mortal enemies Elon Musk and Jack Dorsey both agree it’s also bullshit, well, it must be.

I have great hopes for the breaking of the world. We simply need each other. We need signs of life.

“I have split the infinite. Beyond is anything.”

I’m sorry to have to be the one to tell you this. There is such a thing as bad art, and bad poetry. And if there’s bad art, there’s evil art. Quality, even in the philosophical sense, is a real thing.

Meet the good guys in our story.3

In 1943 Australian poets James McAuley and Harold Stewart collaborated in creating their country’s most famous literary hoax. Both had established themselves as poets before the outbreak of World War Two. During the war, they crossed paths at the military barracks in the city of Melbourne, where McAuley was a lieutenant in the national militia and Stewart was serving with Army Intelligence. McAuley was a devout Christian and staunch anti-communist who would go on to be a well-known academic and a successful poet. Stewart wrote long metaphysical poetry that would be classified by critics as neo-classical; his verse was influenced by Carl Jung and eastern religion, and in later years he became a Buddhist and settled in Japan. If you know anything about modernist poetry, you will not be surprised to learn that both of these men despised it.

They invented a poet they called Ern Malley, who had only recently “died” at the tender age of 25, but not before completing a cycle of modernist poems called The Darkening Ecliptic. McAuley and Stewart, of course, had penned this cycle themselves, as well as a very moving letter from Malley’s also-fictional sister explaining his tragic death. The collection was sent off to a prominent journal called Angry Penguins. The two men seem to have enjoyed the process of creating what would become some of their most enduring poetry, all of it a lie.

“We opened books at random, choosing a word or phrase haphazardly. We made lists of these and wove them in nonsensical sentences. We misquoted and made false allusions. We deliberately perpetrated bad verse, and selected awkward rhymes from a Ripman's Rhyming Dictionary."

In speaking of the sort of poetry they were mocking and creating, McAuley and Stewart had this to say regarding modernist poetry and their secret project in the June 25, 1944 issue of Fact magazine:

“Their work appeared to us to be a collection of garish images without coherent meaning and structure; as if one erected a coat of bright paint and called it a house. However, it was possible that we had simply failed to penetrate to the inward substance of these productions. The only way of settling the matter was by experiment. It was, after all, fair enough. If [Angry Penguins managing editor] Mr. Harris proved to have sufficient discrimination to reject the poems, then the tables would have been turned.”

Instead, Harris dedicated an entire issue to the conveniently martyred “Ern Malley”, writing a gushing introduction himself in which he called Malley one of the two greatest “giants” of Australian poetry. Since this was before poetry had become completely irrelevant in the West, the Ern Malley hoax was picked up by newspapers. It continues to be written about today, as here. We will not concern ourselves here with all the fallout of the affair, although you may enjoy doing further research into the hoax. We will, however, explore further the manner in which the two men wrote their verses, poems which were proclaimed by so many to be brilliant, and which many still try to proffer to readers today as outstanding modernist poetry, as if they displayed unconscious poetic genius.

Before publishing, editor Harris made a small correction to the last line of the cycle, one he thought obvious to make because he was taking the work seriously.

He published “I have split the infinite. Beyond is anything.”

The line he was actually sent read “I have split the infinitive. Beyond is anything.” Splitting the infinitive is a behavior frowned upon by grammar teachers. McAuley and Stewart were showing their hand, but Harris was blind to see it, because the artistically and ethically bankrupt method the men used to write the poems merely replicated the way people had really begun to write poetry. There was no more serious or earnest way to write; to this day, poets are taught to write as described below, but in more pretentious the-emperor-is-too-clothed language. Alas. Good poets (in fact, all good artists) must work against this now standard navel-gazing method of creation, especially if they were educated in secular schools or erstwhile bohemian districts.

According to McAuley and Stewart,

“Our rules of composition were not difficult:

1. There must be no coherent theme, at most, only confused and inconsistent hints at a meaning held out as a bait to the reader.

2. No care was taken with verse technique, except occasionally to accentuate its general sloppiness by deliberate crudities.

3. In style, the poems were to imitate, not Mr. Harris in particular, but the whole literary fashion as we knew it from the works of Dylan Thomas, Henry Treece and others.”

As for those who, once they had discovered the hoax, defended the merits of the work anyway, the two poets had this to say:

“For the Ern Malley ‘poems’ there cannot even be, as a last resort, any valid Surrealist claim that even if they have no literary value (which it has been said they do possess), they are at least psychological documents. They are not even that. They are the conscious product of two minds, intentionally interrupting each other’s trains of free association, and altering and revising them after they are written down. So they have not even a psychological value.”

At this point, you must be anxious to taste some of their wares. Here is a sampling of The Darkening Ecliptic:

Though stilled to alabaster

This Ichthys shall swim

From the mind’s disaster

On the volatile hymn.

…

My white swan of quietness lies

Sanctified on my black swan’s breast.

…

Princess, you lived in Princess St.,

Where the urchins pick their nose in the sun

With the left hand.

The sort of poetry MacAuley and Stewart mocked is relentlessly introspective, all belly-buttons and belly-button lint. The language has certainly been ritualized here, but nothing more. Music has direction and tries to carry you somewhere; cacophony breaks your senses into paralyzed pieces.

These verses bring images into our minds, regardless of their quality. So does anything created by artificial intelligence. Depending on our definition of real, they are as real as any other verse.

Other questions must be asked, not about reality or accuracy or data, but about truth, beauty, and goodness.

Books have always been sus.

Othello has been a controlled and suppressed text for a long time. So has other Shakespeare, for that matter; bowdlerization, after all, started with Shakespeare4.

The beautiful thing about a passage like this…

Even now, now, very now, an old black ram Is tupping your white ewe. Arise, arise! Awake the snorting citizens with the bell, Or else the devil will make a grandsire of you.

…is that there will always be those who will be offended, and it will offend differently in 2020, in 1970, in 1920, in 1870, in 1820. It’s fun to imagine the scenarios.

The important thing is that versions of expurgated (yes, that’s the official term for this process, with whatever author) Shakespeare abound, among the fundamentalists and the woke. And the woke fundamentalists. Thanks to the Bowdlers alone, generations of children were fed a Shakespeare whose characters did not blaspheme, and certainly never spoke of country matters.

The most commonly read translations of Aeschylus gloss over faggotry and pederasty.

In fact, most older English translations attempt this elision5 with all the ancient Greeks, as the Romans often did in their day. And this is true not only of the poets like Aeschylus and Sophocles and Euripides, but of the philosophers and historians, Aristotle and Thucydides and Herodotus. To obscure such things, even if only so that the young may digest it, is to change the material itself: it is significant that Ganymede was seized by Zeus, then made a god, when “his boyhood was in its lovely flower”. Human society imitates and is justified by divine society; the twelve-year-olds in Victorian British public schools might have benefited from knowing what price the older men in their lives might require to make them gods.

It does not do to present a book as Aristotle when it’s not, even if the justification is that the expurgations are incidental to his really important ideas. Teach from excerpts. Share summaries. That’s half of what teaching Plato is already. Or throw them in the trash. Just don’t present the bowdlerized as the real work of the author, or that work as best as we can reconstitute it.

Constitution is relevant here. Books have always been cobbled and re-cobbled together again and again, excised and resized and massaged. The definitive manuscript exists, then Q is found. Parchments are found and lost and found. New editions come and go. Editorial courage now stands taller, now fails.

That’s not even to speak of authorial variation.

John Calvin published five different Latin editions of his Institutes, expanding on it with each new edition. The 1536 edition was just 6 chapters long, and the addition of 17 shorter chapters in 1539 doubled the book’s size. Four more chapters were added in 1543, and then only minor changes made in 1550. But the final, 1559 version was fully 80% larger than its predecessor. In addition to these Latin editions, Calvin also created French versions that, while very similar, were not strict translations – they taught the same doctrine, in the same order, but sometimes said things in different ways.

It is the final Latin 1559 version that most translations are based on, including the two best-known English-language translations: the 1845 Henry Beveridge, and the 1960 Ford Lewis Battles translations.6

With the advent of print-on-demand, new versions of the shorter, less developed Institutes flourished.

D. H. Lawrence wrote three versions of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and that’s not to speak of the expurgated versions. That anyone would rather have read an expurgated version rather than skip the book entirely, I struggle to understand. I suppose the need to have fashionable conversation was overwhelming.

Then there’s straight-up censorship, or the greedy editorial hand, which amount to the same thing.

In the 16th century Italian readers only had access, unless they smuggled their books, to an expurgated version of Desiderius Erasmus’ Adages. The version commissioned by the Council of Trent so thoroughly purged Erasmus’ book that the edition is sometimes given with the publisher’s name in place of the author: Paolo Manuzio’s Adages. This was, it was thought by the pious, better than the total ban that had preceded it. Erasmus had been dead some thirty years at that point, and so would have nothing to say.

Speaking of book smuggling, this is an ancient and honorable vocation of roguery, and it will be relevant to us later on.

The final chapter of A Clockwork Orange was omitted from American editions for over twenty years from initial publication, until 1986. The vast majority of readers would have been oblivious of this fact. If asked “Have you read A Clockwork Orange?”, a blithe and simple “Yes” would have been their answer.

There are paraphrases and retellings of the Bible which purport to be, rather than paraphrases and retellings, actual Bibles, and their readers believe they’re reading Bibles. There are Bibles altered for “inclusivity” and others for “just language”, and here publishers and readers believe that an essential message has been preserved, that they are still Bibles, like Aeschylus without sodomy is still Aeschylus.

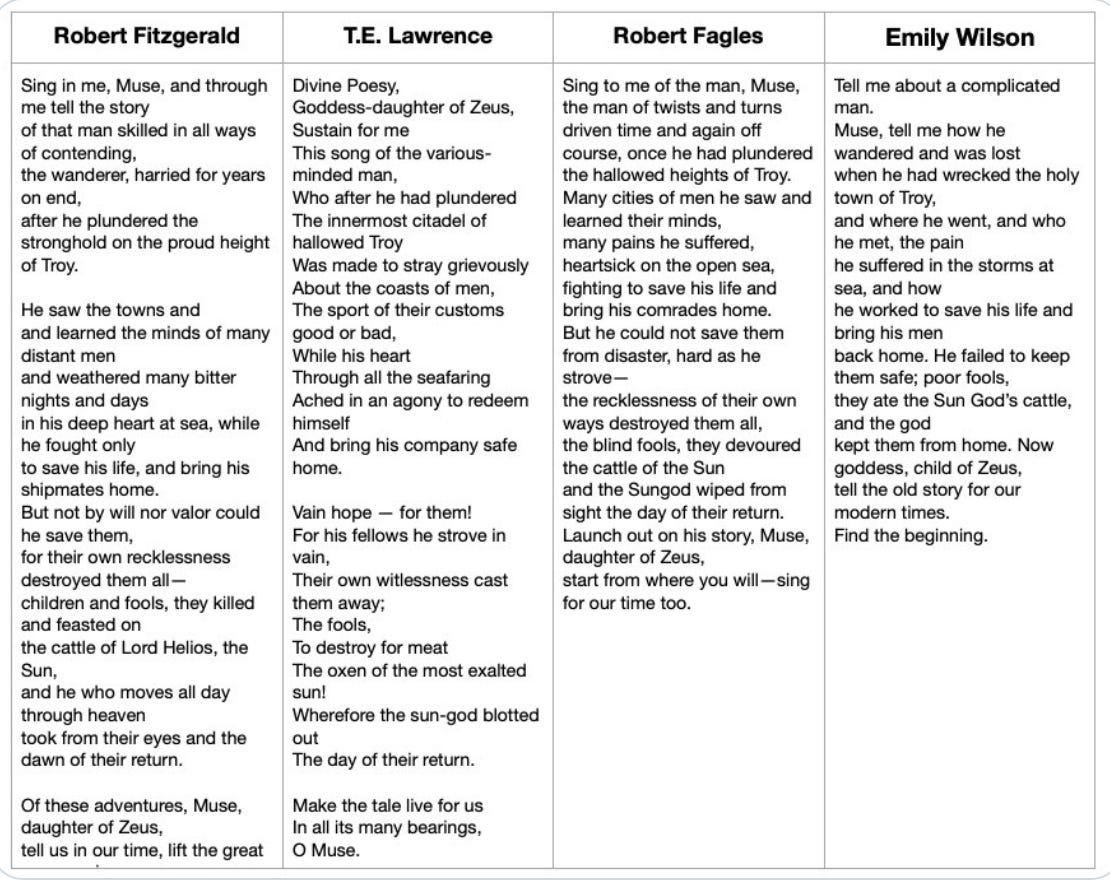

Why have classicists, literarians, and book lovers of all sorts gone to war over Emily Wilson’s new translation of the Iliad? Because any new translation backed by a major publisher has a chance to be the version meant when young people say “Yeah, I’ve read the Iliad.”

This graphic show four different beginnings to Homer’s Odyssey, including Wilson’s:

This would be a far sparser Odyssey, one in which “the man of twists and turns” or “the various-minded man” became simply “a complicated man”. As Spencer Klavan put it in an article entitled Homer Without Heroes, “Wilson’s Iliad is so deflated that it’s hard to tell what Homer’s characters are fighting for.”

This would be a version in which Wilson’s self-stated agenda of “making visible the cracks in the patriarchal fantasy” means that the metaphoric liveliness of “rosy-fingered dawn” becomes the the awkward and unmagical “Dawn appeared and touched the sky with roses”.

This is all to say that there are always agendas at play, on the part of authors, translators, publishers, sellers, politicians, commissars, bureaucrats, priests…books have always been sus. That had to be navigated then, and it has to be navigated now.

Amazon could change a book you “own” on your Kindle without your ever knowing. How can you trust what you read?

The internet treats you as either a consumer or a product, and feeds you information motivated by commerce. How can you trust what you read, what you view?

Reddit is so popular, and appealing to so many, because it is a sort of independent freeholder’s kingdom, built by its own denizens. It reminds one of the old internet, but instead of a wild free-for-all of tiny fiefdoms, with villages and inns scattered about, Reddit is a great walled city, like the other globalizing walled cities of the internet, except that it grows by promising (and delivering) freedom. By the Reddit ethos are Redditors kept safe, and at this point maintaining that ethos is the only way to keep and grow its population, to keep the other hungry kingdoms at bay.

For a while now, the best way to find reliable information online has been to append “reddit” to a Google search. And where will that take you? Somewhere where other humans, unmotivated by SEO, are talking about what you need to know, pointing to this resource or that document.

The unbearable lightness of being.

The internet is breaking apart, and it will bring all information down with it. Even books. Especially books. Nothing can be trusted. But I have great hopes for the breaking of the world. We simply need each other. We need signs of life.

Nothing ever could be trusted. Not fully.

Perhaps at this point you think that I am a skeptic, or a nihilist, or that the world is too much with me.

Not so. Not only am I an optimist, but I embrace a hermeneutic of generosity. I seek after, I long for, I yearn for, I pine after positive best-light interpretations. I just don’t want to ask of any made thing what it cannot deliver. I want to recognize its true nature and make the best of that.

What are the things I can trust the most? Those with which I’ve made pacts and covenants, those which are closest to me, those which I can see best, have seen best, and have been seeing best.

This is why I trust my wife. Although I know that the possibility of unfaithfulness exists in some remote but innegable way, it has become almost inconceivable to me. I’ve been looking at her for twenty-five years and more now. But this trust is not some intense or hard-wished thing. It is comfortable and relaxed, and well aware of her weaknesses and failings. In fact, I can say that I fully trust her regardless of (not in spite of) her weaknesses. I fully trust her, even though I do not at all trust her to wait for the movie to reveal its plot to her. Do you see what I mean by trust?

This is how one must look at the world, I think. The only reason mankind has suffered an existential crisis over the unknowability of reality is that men desired to be gods. Immodesty and immoderation has led us to ask too much of ourselves and our world.

To affirm the possibility of corrupted knowledge or information is simply to affirm our humanity. The task, then, is to never be content with this, but to never succumb to the crack-up of perfectionism either.

I trust the books that I’ve found for myself in the crannies of used bookstore basements; yet only so far. I trust older editions; yet only so far. I trust the books given to me by friends; yet only so far. I trust the books handed down to me by the men and women I’ve covenanted with, both living and dead; yet only so far.

This is real trust. Not some ideal Platonic form of trust, but a substance of things hoped for and evidence of things not seen. A knowing in part, through a glass darkly. An understanding that the things which are seen were not made of the things which do now appear.

The internet is breaking apart, and it will bring all information down with it. Even books. Especially books. But I have great hopes for the breaking of the world, because of the making of many books there is no end. We simply need each other. We need signs of life.

Have you ever wept over the loss of all the books of antiquity? Perhaps you should. What we have today is a tiny tiniest fraction of the literary achieve of classical man. But what of it? It is one more grief in a grievous world, and one more beauty in a beautiful world. It is a death and a resurrection. It is nothing to be afraid of. I have great hopes for the breaking of the world.

YouTube philosopher Jared Henderson is going to focus on localism, not only physical, but internetal. And I think that’s wise. He’s going to buy e-books and pdfs from trusted sources, and store them himself. That’s smart.

KillDevilHill.com is gone forever. It died a lifetime ago. I get a little sad every time I think of it, but I almost never think of it.

Book smuggling has been a thing since well before the invention of the codex. One of the high points of book roguery was the Reformation era, the time of Desiderius Erasmus and Jean Calvin and Casiodoro de Reina, of censorships and inquisitions and spy rings and royal publishing licenses and pamphleteering.

I expect that the next generation of book dealers with be former Redditors. Rather than sell you access to the library of a great kingdom, they will sell you the actual thing, whether codex or pdf. They will be purveyors of e-books and audiobooks, and will trade on their reputations. They will know things, like booksellers of old, and will tell you before you buy that this is the third edition, which removed the dream sequence but added a meditation on divinity. You will buy from them because you know them.

I have great hopes for the breaking of the world. We simply need each other. We need signs of life.

Thus endeth the lesson. For real. Above was the end of this post. Below I tell you why these things have been on my mind, and it’s because I want to sell something. I want to be one of the book dealers I spoke of above.

Here is a sign of life:

I’m creating a new translation into English of Don Quixote by Cervantes. I want to pre-sell a thousand copies, and I hope you’ll buy one. If you’re not already a reader of this Substack, but you got to this point, perhaps you now feel as if you know me. Not only will I be your book dealer, but your author, creature of your patronage.

As a testament to my love for the Quixote, I leave here links to my translation of chapter 1, as well as this link to a poem I wrote based on my translation of Marcela’s speech on beauty.

Link to support project and get a book.

This is an Audible/Amazon link. I get nothing from it, not even royalties. If you want me to get royalties and feel like an accomplished writer, buy Christian Pipe-Smoking: An Introduction to Holy Incense, Well Met or Made in the Image from Amazon, or Made in the Image directly from Canon Press.

The only uncertainty in this declaration lies in the fact that the current powers of our world will not want to see it broken, and the possibility that the may succeed in repressing/controlling AI.

This next bit is taken from my upcoming poetry textbook from Roman Roads Media, which I hope will be out this spring. You can join their email list here to get updates, but you better believe I’ll be giving updates through this Substack as well.

The term is inspired by the 1836 Family Shakespeare, edited by the Bowdler siblings. https://www.etymonline.com/word/bowdlerize

If you doubt me, start here.

https://reformedperspective.ca/calvins-institutes-which-edition-to-read/

Wow, that's quite the post. I enjoyed it. Incidentally, Adam Curtis's "The Century of the Self" is also excellent.