Protestant Ordinariness Is the Key to Good Art

Here's a little sketch inspired by Louise Moillon and Chocolate Knox.

This piece is part of The Choc-Board, a 30-day writing challenge from my friend Chocolate Knox. His personal objectives for the next thirty days, starting today, are to “diagnose the ordinary until it reveals the extraordinary - from kitchen sinks to AI, from marketing, and branding to worship services, and Calvinistic free markets, from business plans to family prayers. Every moment carries more meaning than we've noticed if we learn to look with the right eyes… Prophetic, Priestly, Kingly eyes. Goal? At least three sentences minimum per post. No topic off limits. Literary gumbo.” You can follow Chocolate Knox’s Diagnostic Doxology on Substack, as well as his profile on X, which is where I think most of The Choc-Board interactions will be happening. Several other writers have hopped on board.

Be warned. This thing is sketchy. It could be a book, but I’m going to get through it in two pages, with lots of pictures. Do with it what you will.

I’m not much of an art historian, but enough has apparently percolated through my mind that when I came across this painting on my X timeline I immediately knew it was painted by a Protestant. I will not be writing about art history, but rather the significance of that recognition of Protestant visual art, and the place of the arts within Protestant culture.

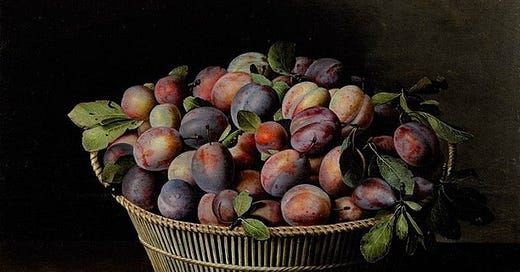

This is Basket of Plums, a painting by 17th-century French painter Louise Moillon. The X feed of the Journal of Art in Society posted the painting last night with the words “Louise Moillon achieved fame with her beautifully precise still-lifes ~ here’s her Basket of Plums (1629)”. How did I recognize Basket of Plums as having been painted by a Protestant?

Obviously, I’d been primed by the date, but even knowing she was French, I was confident as I went to Wikipedia that she’d be a Huguenot. The painters who inherited the Northern Renaissance, the Reformation, and the work of Flemish and Dutch realists painted like this: lively, robust, full of contrast, staged yet realistic. They were not always cheerful (memento mori), but they were always robust. Southern and Catholic still lifes were more decadent.

On the left is Diego Velazquez’ Still Life (one of many), and on the right Caravaggio’s Still Life with Fruit on a Stone Ledge (c. 1605). Both were baroque painters. Here are some human figures painted by Caravaggio.

On the left is Bacchus (1589), and on the right Boy Bitten by Lizard (1594).

Without getting into the weeds of how great many baroque painters were, or how northerners may have influenced Caravaggio’s stronger later movement into still-lifes, or how truly brilliant a work the Binding of Isaac is, I think the casual viewer will be able to detect how much humanism and paganism are embedded in the expression of these paintings. This is the case generally for Roman Catholic painters of the period, and I encourage you to research for yourself; let me know in the comments below what you think.

Louise Moillon was not a particularly prolific painter. Well, she was, but during a brief period. She did nearly all her painting in the decade before her marriage at around age 30. Here are three paintings she did using human figures.

This is where we get to ordinariness.

Caravaggio was brilliant. He pre-dated many of the better-known Dutch still life painters, as he did Moillon. Here is his Martha and Mary Magdalene, from around 1598.

The painting is allegorical, and full of significant symbols, but still robustly quotidian. In fact, that ordinariness is part of the message of the painting.

Caravaggio is considered a baroque painter, and a father of the baroque. This is where baroque ends up, however, and is likely what you think of when you think baroque: the tasteless horrors of rococo.

Mid-stage:

Full rococo madness:

I believe the viewer will be able to see the path that a godless humanism takes.

Let us return to Moillon’s ordinariness. I will put one of Moillon’s paintings of women beside Martha and Mary Magdalene.

Although Moillon was held in high regard by her peers, and employed trompe l’oeil to great effect in her paintings of objects, I believe the viewer will agree that Caravaggio’s skill with the human figure are evident prima facie. In other words, there’s probably a reason Moillon principally stuck with still lifes. Putting that to the side, let’s compare the two paintings.

Caravaggio’s painting is an imagined scene, but set directly in a Biblical story we all know. He painted many scenes from Scripture and ancient stories, but this one is unique in that, if it took place, would take place behind the scenes of the story. It is charming in its ordinariness, leaning into the relatability of Martha and Mary , but at the same is anxious to communicate, full of symbol and significance, full of moral.

Here is where we get to how I knew the painting was Protestant.

Moillon’s painting is a celebration more than it is a communication. Of course, there is a message. It’s a work of fine art, after all. There is a message, but no moral. It says simply, life is beautiful. Fruit are beautiful. Women are beautiful. And not in a bouncing boobies way, like the cult-of-youth stuff that humanists produced, and that even Caravaggio was occasionally subject to. Rather, women are ordinarily beautiful.

One of the fascinating aspects of how many view Reformed Christians today is the lens of dourness and sourness. It is, at least historically, a slander. The Wikipedia article on Moillon says she was brought up in a “strict Calvinist family”. Words like “strict” append themselves to Calvinist in almost knee-jerk fashion. The contemporary human in almost incapable of writing out the word Calvinist neutrally. If it’s Calvinist, it’s strict. I might call this the Nathaniel Hawthorne effect, a mythology of Puritans created by unitarian New England transcendentalists that has been dismissed, with facility, by many others, including C. S. Lewis.

Calvinists were known for being joyful, and full of feasting. Here again I encourage you to do your own research (Douglas Wilson could be a good starting point), and I will rely only on Moillon’s paintings. These are celebrations.

Celebrations of work, or ordinariness, of plenty, of community. In each of these paintings there is a vendor, and one other woman. Take a moment to think about the relationship between the women in each painting.

Moillon’s still lifes are also extraordinarily ordinary.

These are celebrations of life itself, of plenty, of God’s good creation. They are optimistic and glad, and a natural expression of Protestant theology.

So what happened? Where have all the Protestant artists gone? I use the word artist broadly, by the way. I despise the habit of calling painters artists but musicians musicians. They’re all artists. So I’m not just asking about painters. Where’s the Protestant art?

Well, we accepted that the world is the world of humanists. This is not our Father’s world, but a world where evil prevails, biological life a burden, and the life of the mind the only one worth living.

We accepted that the world is propositions. Cogito, ergo sum. The world breaks apart in irreality, and we end up agreeing with the worldings: art, like God, is dead.

We accepted that things are going from bad to worse. Jesus is savior of souls, but not the cosmos. Creation groans for the unveiling of the sons of men, sure, we have to say that because it’s in Romans, but what Creation really craves is death by fire. Cupio dissolvi.

We have accepted that ordinary is a burden. Life is boring, and deeds and apples are meaningless. For God’s sake, cupio dissolvi.

If we are to be optimistic and glad, if we are to believe the Gospel, we must rejoice in God’s good Creation. That’s were good art comes from, from rejoicing in Creation to the point that we can’t help but express this in sub-creation. We’re made to be makers; makers make. Art is worth pouring our excellence into. Cultivating excellence takes everyday living and everyday dedication, and through it we may glorify the everyday.

We cannot be a community of faithful Christians, we cannot be faithful as the Church, if we are not valuing art and producing artists. This will be a fruit of faithfulness, and striving toward it will help us to become more faithful.

If every birth is the birth of an eternal soul, every apple eaten is fuel for forever. Sometimes, people bake apples with brown sugar and raisins. Have you ever eaten a baked apple? Delicious. Worthy of a poem, of a painting, of a song. Rejoice in the ordinary, friend.

<29>