Is It Time For The Novel To Die?

The Conflation Unto Death; Can stories be told that are not novels?

Robert Charboneau has posted a short critique of David Morris’ New York Times op-ed The Disappearance of Literary Men Should Worry Everyone. In a nutshell, Charboneau argues that Morris is a bad writer and bad reader who has mislocated the trouble. For Charboneau, the problem is not one of representation or consensus, but of imagination.

People are certainly talking about men and reading. Three years ago I made a video entitled Why Don’t Men Read Female Authors? Out of nowhere, starting in July of this year and bumping up even more in November, this old video started garnering interest and discussion in the comments. I imagine that similar content across YouTube has experienced a bump.

This week I had a conversation with two friends, one of whom is a professor, about a new graduate program that hybridized a particular discipline with “Letters”. When the non-professor asked what was meant by Letters, the professor sort of came up short and repeated the question, honestly, to himself: “What are Letters?”

All that is meant by Letters, of course, is Literature. It’s a term I often use, as it’s natural for me because of my Latin (Brazilian rather than Imperial) background. I prefer it, as apparently the organizers of this new graduate program do, because it retains the full meaning of what should be meant by the word literature. Alas, when most people use the latter word they overwhelmingly mean one thing: novels.

When Morris bemoans the lack of literary men, he means novelists and novel readers. In fact, his op-ed is not about literature at all, but about one band of literature. The word “fiction” is used ad nauseum.

Literature itself is in crisis (i.e. the problem is not “men”), and I believe that is because the novel is in crisis. It may have run its course.

What follows is a series of disparate thoughts regarding the novel.

I, for one, would be fine with the death of the modern novel. Art forms come and go and come again. The death of the novel would not be the death of story, or character, or prose, or lyric, or imagination. Moderns tend to overestimate the importance of the novel simply because they are familiar with it, and unfamiliar or uncomfortable with medieval and ancient literature.

One limitation of the novel is its intimacy, which is both strength and weakness.

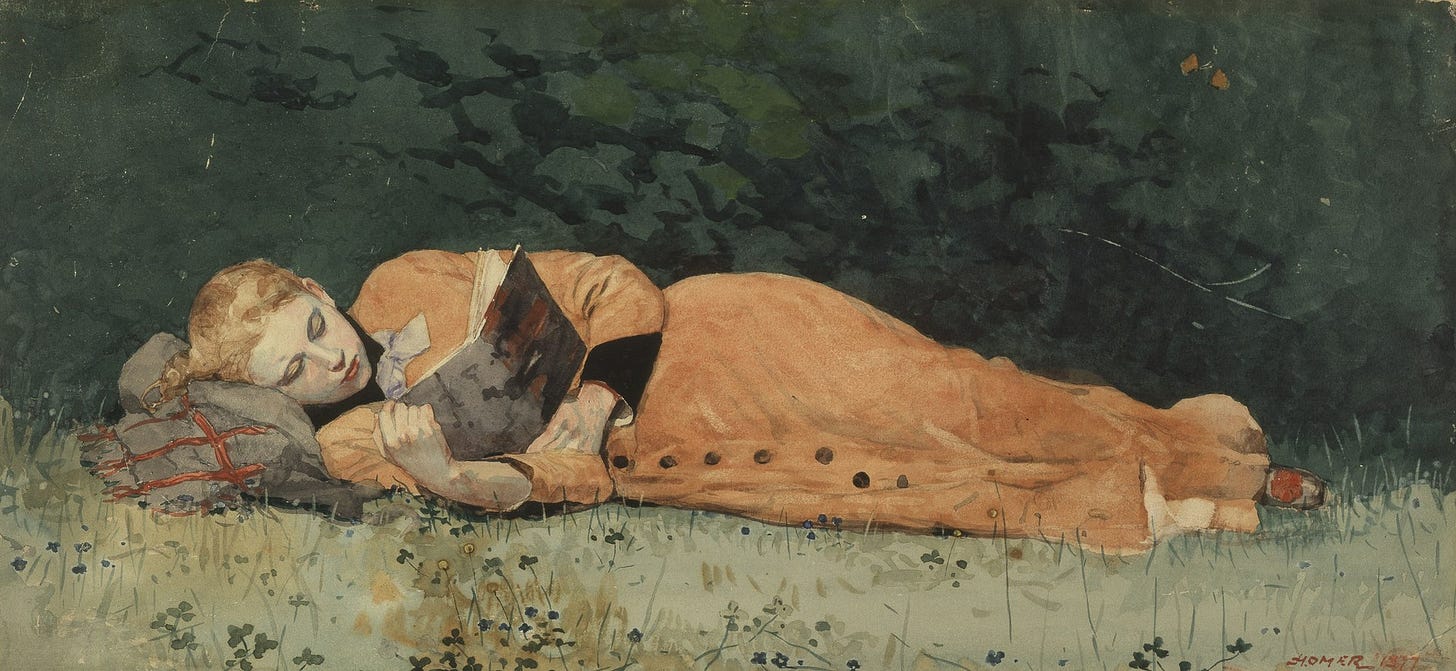

For most of human history, the assumption of those who could read was that the words were meant to be read aloud, often socially or to groups. Our default setting, that reading is for individual and silent absorption, did not become dominant until the 19th century. A good example of this is the manner in which poetry has been written and read: not until the 20th century did forms of poetry emerge that work best on the page, read by individuals, each having their own unique experience with the work. Such is the novel.

At university I was taught a certain truth, but through the lens of the Enlightenment: novels were thought decadent by many in the 18th and early 19th century. The story of the emergence of the novel is often told in conjunction with the myth of progress, that is, modern novels are a natural and necessary growth and early novel-despisers were unenlightened troglodytes. The manner in which novels were consumed began to change as Rousseauism/Voltairism/Romanticism dovetailed with increasingly cheaper book production. Novels became more niche, and many were written for private and intimate consumption. Gothic romances emerged. People, especially women, started reading privately, and *gasp* even in bed. If we examine the perception that novels were decadent with some sympathy rather than chronological snobbery, we might grant that it doesn’t take much for novels to become masturbatory. I do not mean by this that novels are a literary spank bank; rather, readers often use them for affirmation, confirmation, soothing, and private vindication. This is harder to do with literature written for the open air, or for family reading.

I love novels. I was raised by Lord of the Rings. And of course, as soon as I say that, serious literary people dismiss me. Why?

It is interesting that many of the novels favored by Christians (Tolkien, Lewis, O’Connor, Charles Williams, MacDonald) have something of the medieval romance in them.

Lewis may actually be a divider of waters. Think of the "space trilogy”. The whole thing is very medieval. Suggestion: if Perelandra is your favorite, you are a lover of romance; if you prefer That Hideous Strength, you are a lover of the modern novel.

I love novels, but I hate Cormac McCarthy. Well, I read a bit of him once and hated it; nihilism oozed off the page. So I hate five pages of McCarthy. Because of his recent fall from grace, over the past few weeks I’ve read several articles and watched several videos discussing his legacy. One philosopher I enjoy watching on YouTube made a video on the subject, and at the beginning outlined the various audiences who might be interested in the video: those who love McCarthy and think his behavior should have little or no effect on how we view his art; those who love McCarthy but think his legacy should be regretfully destroyed; those who have never read McCarthy but are curious. He explicitly named one audience for whom his video had not been made: those who did not enjoy McCarthy’s work. These he dismissed as unserious. I don’t take this personally. I am dismissive of McCarthy, and turnabout is fair play. But surely this way of thinking is myopic. McCarthy is such a titanic genius that no serious person could dislike or depreciate his work? The synecdochic conflation of the novel with literature has destroyed the critical and artistic mind of the literary set.

I love novels. When I read them, I do not require flowery or poetic prose, fantastic or fabulous scenes, or high medieval romance, as you might be imagining. The truth is, dry prose is very much to my taste; I do not enjoy rococo stylings. What I do require is exaltation, divine striving rather than stoic resignation or nihilism. I can be nihilistic on my own, thank you very much.

Graham Greene is an excellent example of how a dry writing style and plots of administration, bureaucracy, boredom, and crushing quotidianness can elevate the soul.

Certain scholars have been discussing the death of the novel for a hundred years. Some argued that there could be no novel with Götzen-Dämmerung, with a bourgeois world, with Heidegger’s forgetfulness of being, with nihilism, with semiotics, with deconstruction, with with with. The novel has not died, but is much diminished, its compass grown smaller with each repeated “with”, failing to look beyond the encroaching fences.

The novel was born in parody.

The very nature of the written word and the page is changing. It would be self-indulgent to fail to account for it. The least the literary world can do is to not pout about it, but truly beautiful souls will conceive of new novels, and evolutions upon the form.

There must be imagination. At its most fundamental level, imagination asks: what’s on the other side of that?

A reminder that Aristotle’s word for imagination was phantasia.

I do not wish for the death of the novel. However, if people insist that literature = novels, the novel will die. Like anything, it cannot flourish if it is not in a good place, and good places are always relative to the rest of the world.

Articles like David Morris’ express upset that people are not eating anymore, but the diet being rejected is cotton candy. Eventually people will find something they can sink their teeth into. Is “reading fiction” really our hope for how letters and story can exalt mankind?

I shouldn’t say it’s cotton candy. “Serious” novels aren’t candy. They’re vodka, which is the dumbest liquor, the more flavorless the higher the perceived quality, existing only for a flash of brief warmth, and the possibility of oblivion.

The best way to love something is to hold it loosely. The same goes for fostering flourishing. If the academy or the anointed literati impose a certain mode of reading, they necessarily impose a certain form of writing. It is preferable to foster creativity and artistry broadly (yes, this is done through exposure, which does imply a more or less defined canon). The modern novel is so narrow, friends. It is being choked by over-curation. What is needed now is benign neglect. It will flourish if it comes up from the roots.

Let men decide what they want to read and write. Help men do so. Stop telling them what to read.

I have no faith in the literary establishment to broaden its opinions and sensibilities, much less its publications and promotions. Like most art forms, the novel must seek a parallel economy. It is already doing so. Not surprisingly, men are just as active as women in that economy. More so, perhaps.

In closing, I raise my glass and wish the health of all novelists, essayists, storyists, fabulists, dramatists, rhetorists, poeticists, and all other men and women of speech and letters.

Thanks for reading this, y’all. If you enjoyed it, consider restacking and subscribing. You can also support me by visiting my Etsy Shop, Chestertonian (pictured above), featuring stuff from the brightest literary timeline.

I had a whole second half to my article that I cut, arguing that literature had moved on from fiction and is going back to poetry. The literary man had quit being a novelist, because the genre had grown stale from people like Morris, and was going to become a poet again. I cut it because I felt I was running away with the plot, but here you lay it out much better than I could.

I like your distinction between "letters" and "fiction." It's absolutely true. A man of letters is something to aspire to.